Entity: 01KCJK6Z2CSEBHFJJ34E0BS9WM

PI

Version: 3 (current) | Updated: 12/16/2025, 3:30:00 AM | Created: 12/16/2025, 3:28:09 AM

OCR: Updated 2 refs

Files (2)

OCR Text

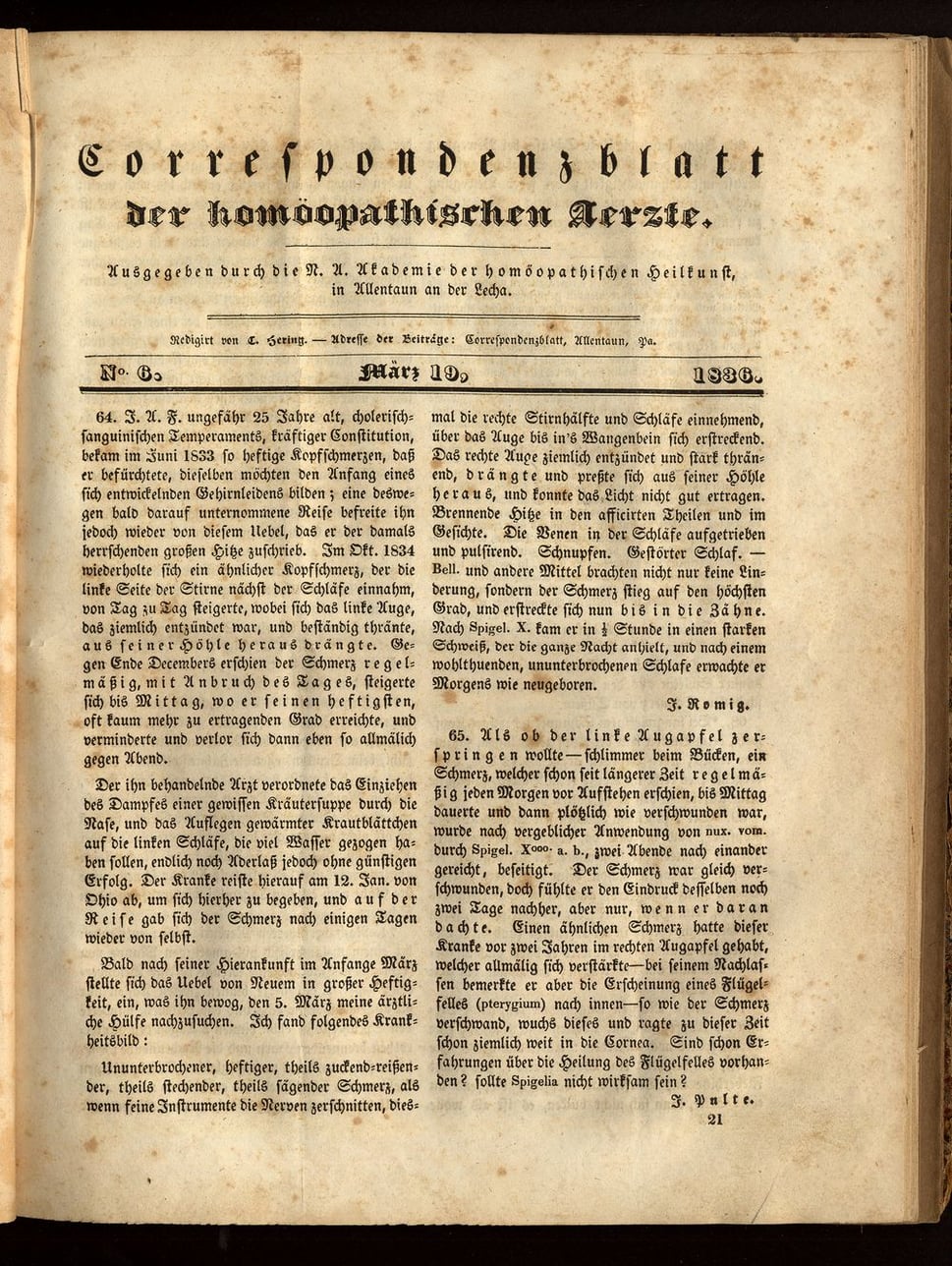

Correspondenzblatt der homöopathischen Aerzte. Ausgegeben durch die N. A. Akademie der homöopathischen Heilkunst, in Allentau an der Lecha. Redigirt von C. Zering. — Adresse der Beiträge: Correspondenzblatt, Allentau, Pa. No. 6. März 19, 1836. 64. J. A. F. ungefähr 25 Jahre alt, cholerisch-sanguinischen Temperaments, kräftiger Constitution, bekam im Juni 1833 so heftige Kopfschmerzen, daß er befürchtete, dieselben möchten den Anfang eines sich entwickelnden Gehirnleidens bilden; eine deswegen bald darauf unternommene Reise befreite ihn jedoch wieder von diesem Ubel, daß er der damals herrschenden großen Hitze zuschrieb. Im Okt. 1834 wiederholte sich ein ähnlicher Kopfschmerz, der die linke Seite der Stirne nächst der Schlafse einnahm, von Tag zu Tag steigerte, wobei sich das linke Auge, das ziemlich entzündet war, und beständig thäunte, aus seiner Höhle heraus drängte. Gegen Ende Decembers erschien der Schmerz regelmässig, mit Anbruch des Tages, steigerte sich bis Mittag, wo er seinen heftigsten, oft kaum mehr zu ertragenden Grad erreichte, und verminderte und verlor sich dann eben so allmählich gegen Abend. Der ihn behandelnde Arzt verordnete das Einziehen des Dampfes einer gewissen Kräutersuppe durch die Nase, und das Auslegen gewärmt Krautblättchen auf die linken Schlafse, die viel Wasser gezogen haben sollen, endlich noch Abreib jedoch ohne günstigen Erfolg. Der Kranke reiste hierauf am 12. Jan. von Ohio ab, um sich hierher zu begeben, und auf der Reise gab sich der Schmerz nach einigen Tagen wieder von selbst. Bald nach seiner Hierankunft im Anfange März stellte sich das Ubel von Neuem in großer Heftigkeit ein, was ihn bewog, den 5. März meine ärztliche Hilfe nachzusuchen. Ich fand folgendes Krankheitsbild: Ununterbrochener, heftiger, theils zuckend-reissen-der, theils schender, theils sägender Schmerz, als wenn seine Instrumente die Nerven zerschnitten, diesmal die rechte Stirnhälfte und Schlafse einnehmend, über das Auge bis in's Wangenbein sich erstreckend. Das rechte Auge ziemlich entzündet und stark tränend, drängte und preßte sich aus seiner Höhle heraus, und konnte das Licht nicht gut erragen. Brennende Hitze in den affizierten Theilen und im Gesichte. Die Venen in der Schlafse aufgetrieben und pulsirend. Schnupfen. Geschüchter Schlaf. Bell. und andere Mittel brachten nicht nur keine Linderung, sondern der Schmerz stieg auf den höchsten Grad, und erstreckte sich nun bis in die Zähne. Nach Spigel. X. kam er in 1/2 Stunde in einen starken Schweis, der die ganze Nacht anhielt, und nach einem wohlthuenden, ununterbrochenen Schlaf erwachte er Morgens wie neugeboren. F. Romig. 65. Als ob der linke Augapfel zerspringen wollte—schlimmer beim Bücken, ein Schmerz, welcher schon seit längerer Zeit regelmäßig jeden Morgen vor Aufstehen erschien, bis Mittag dauerte und dann plöglich wie verschwunden war, wurde nach vergleichbarer Anwendung von nux. vom. durch Spigel. Xxxx. a. b., zwei Abende nach einander gereicht, beseitigt. Der Schmerz war gleich verschwunden, doch fühlte er den Eindruck desselben noch zwei Tage nachher, aber nur, wenn er daran dachte. Einen ähnlichen Schmerz hatte dieser Kranke vor zwei Jahren im rechten Augapfel gehabt, welcher allmählig sich verstärkte—bei seinem Nachlassen bemerkte er aber die Erscheinung eines Flügelfelles (pterygium) nach innen—so wie der Schmerz verschwand, wuchs dieses und ragte zu dieser Zeit schon ziemlich weit in die Cornea. Sind schon Erfahrungen über die Heilung des Flügelfelles vorhanden? sollte Spigelia nicht wirksam sein? J. Walter.

OCR Text

66. Stiche durch die linke Schlafse, bei Bewegung ärger. Vor dem Monatlichen Schwäche auf der Brust mit Ohnmachtigkeit; bei jeder Bewegung große Hinsfälligkeit, wie ohnmächtig; Monatliches zu früh. Spigelia Xoo. in einigen Gaben heilte vollkommen. SPIGELIA. Ich habe in den letzten Jahren meine Collegen wiederholt aufmerksam gemacht auf den bedeutenden Heilnachgang dieses großen Mittels und weitere Prüfungen desselben gewünscht, einerseits weil mehrere Heilungen in Surinam (wo die Spigelia ein Unkraut in allen Gärten ist) mich dazu veranlassten, andererseits weil die hiesigen Ärzte sich die Erforschung der Heilkraft amerikanischer Pflanzen schon längst als eine Hauptaufgabe gesetzt haben. Als obige Beifüglichen einzusehen, fügte ich die hier folgende Uebersicht an, die von mir mit spiegelhaften behandelt hat bei, und eine Mittel zur Heilung unseres Weibesbens: im nächsten Jahr die Zeichen und Angaben (d. h. geheilte Zeichen) der spigelia anthelmintica und marylandica (wenn Zahlmengen seine Zustimmung geben will) in einem besonderen Heft auszugeben, worauf die bisher bekannten Zeichen durch eine gleich große Zahl neuer erneuert werden sollen. Dies war zum Dritte bereit als wir im Archiv XV. 2. die mit der unsern übereinstimmende Ausforderung fanden. Wege die doppelte Erinnerung jeden bewogen seine Tagebücher hinsichtlich dieses Mittels durchzugehen, und mitzuheissen, was bisher verborgen lag. Unsere Freunde in Deutschland sind ebenfalls gebeten, damit wir etwas recht vollständiges geben können, ihrer Erfahrung nach anderer durch eine heimwehreiche Zeitschrift recht bald, oder handschriftlich uns zuzuführen zu lassen, in welchem letzten Falle wir entsprechende Gegenbemerkungen machen wollen. Ohne dies werden alle uns eingefundenen Beiträge durch den fortwährenden, verschlimmernscheinenden Antheil am Gewinn hineinziehen. 67. *Schlagen und Klopfen im Scheitel und unter den Augen, besonders links, bei der mindesten Bewegung und bei jedem Stuhlgange; dabei grüner, dünner Schleim aus den Choanen; Zahnfleisch geschwollen, Schmerz von Süßem. 68. *Bei langwierigem Schnupfen, heftiges Kopfschweh; beim Bücken will der Kopf zerspringen, schlummer rechts; jeden Morgen ärger bis 12 Uhr, dann vergeht's; es reist im Kopfe beim Bücken, so daß sie beim Aufrichten den Kopf halten muß. 69. *Bei 7-jährigem Knaben seit mehreren Wochen Kopfschweh, bald hier bald da, besonders in der Stirn und im Hinterkopf, schlimmer bei Bewegung, bei Laufen, Springen, schon beim Auftreten; beim Bücken ganz besonders, auch beim Schütteln des Kopfes, beim Husten, bei jeder Erschütterung, schon bei Geräusch, ebenso in der Öffnisse (und beim Bewegen des Mundes?) Oft wird er dabei bläf im Gesichte und blau um die Augen; manchmal bis zum Brechen äbel. 70. *Jeden Morgen Augenschmerzen, dann Stechen im Kopfe, Gesicht, Zähnen und Nachen; eine Woche später noch ausserdem: Kälte und Hisse ohne Durst, des Nachts; eine Woche später: jede Nacht Fieberhöhe mit Durst, das Kopfschweh klopfend an einer Seite, kann sich nicht bücken, es ist als wolle der Kopf abfallen; Klopfen überm linken Auge, Bremmen u. Stechen darinnen, fängt Morgens hinten in den Augen an und kommt endlich bis nach vorn; das Auge ist kleiner mit etwas Geschwulst, (dies ist ähnlich mit dalem, auch squilla) den ganzen Tag noch sieberhaft, trockne Lippen und weiss beschlagne Zunge. Dies ganze Leiden, nach drei wöchentlicher ununterbrochener Dauer, verschwand in wenig Stunden ganzlich, nach einmaligem Riechen an Xo. 71. *Heftiger Gesichtsschmerz bei einer Frau zar- ter Constitution; fing an als Zahnschmerz, geht noch von den Zähnen aus, die sehr empfindlich sind, besonders die Schneidezähne, doch nur linker Seite; es schliesse vom Oberkiefer nach allen Richtungen, äußerlich verbreitet es sich über die Wangen, Backen, Schläfe, ist ein anhaltender dumpfer Schmerz mit Brennen unter dem Auge im Knochen, war früher ein äußerliches Brennen auf thalergrossen Stellen am Oberkiefer. Der Anfall wiederholt sich oft zur selben Stunde des Tages; es macht auch noch Kopfschweh, ist nach jedem Essen schlummer, ärger beim Niederlegen; sie kann gar nicht auf der schmerzhaften Seite liegen; so bald es warm wird ist der Schmerz ärger. Dabei anhaltende Appetitlosigkeit. Zweimalig Riechen an Xo half. 72. *Zahnweh bei einer Schwangeren, mit unangenehm von unten aufsteigendem Gefühl, als solle sie bersten, wie Luft im Kopfe, als sollten die Augen aus dem Kopfe springen. 73.*In mehreren hohlen Borderzähnen, unregelmäßig eintretender Schmerz, brennend, zuckend, die Zähne wie lose und länger; bei Berührung ein kaltes Gefühl, beim Drüften gegen die Zähne schlummer, besonders arg beim Bücken; zog nach dem Halse, (in den Mandeln und Drüsen Brennschmerz) ebenso zog es nach Ohr und Schlafse rechter Seite, so daß sie oft nicht mehr wusste wo der Schmerz war; dabei Kopf heiß, Gesicht blau, Füße kalt. Nach vielen andern vergebenen Mitteln half Xo sehr schnell; eine Rte Gabe nach etlichen Tagen bei wiederansangendem Schmerz. 74. Nach versilberten Merkurialpilzen entstanden bei einem melancholisch phlegmatischen Manne von krofulössem Habitus, eine Menge heftige Beschwerden; hepap. s. c. besterte binnen zweien Tagen nur die allgemeine Schwäche und das Leibweh, minderte den Speichelfluß; chin. binnen 3 Tagen den dunkelrothen brennenden Harn und die Nachtunruhe; spig. heilte folgende, dann noch in gleicher Stärke übrigen Beschwerden sehr schnell und entschieden: *Uebler Mundgeruch; Stechen in den Kiefern und

Version History (3 versions)

- ✓ v3 (current) · 12/16/2025, 3:30:00 AM

"OCR: Updated 2 refs" - v2 · 12/16/2025, 3:28:10 AM · View this version

"Added to parent 01KCJK6ZB20FHD1VRQZE3V6WDZ" - v1 · 12/16/2025, 3:28:09 AM · View this version

"Initial discovery snapshot"

Additional Components

book_19.txt

BOOK XIX TELEMACHUS AND ULYSSES REMOVE THE ARMOUR—ULYSSES INTERVIEWS PENELOPE—EURYCLEA WASHES HIS FEET AND RECOGNISES THE SCAR ON HIS LEG—PENELOPE TELLS HER DREAM TO ULYSSES. Ulysses was left in the cloister, pondering on the means whereby with Minerva’s help he might be able to kill the suitors. Presently he said to Telemachus, “Telemachus, we must get the armour together and take it down inside. Make some excuse when the suitors ask you why you have removed it. Say that you have taken it to be out of the way of the smoke, inasmuch as it is no longer what it was when Ulysses went away, but has become soiled and begrimed with soot. Add to this more particularly that you are afraid Jove may set them on to quarrel over their wine, and that they may do each other some harm which may disgrace both banquet and wooing, for the sight of arms sometimes tempts people to use them.” Telemachus approved of what his father had said, so he called nurse Euryclea and said, “Nurse, shut the women up in their room, while I take the armour that my father left behind him down into the store room. No one looks after it now my father is gone, and it has got all smirched with soot during my own boyhood. I want to take it down where the smoke cannot reach it.” “I wish, child,” answered Euryclea, “that you would take the management of the house into your own hands altogether, and look after all the property yourself. But who is to go with you and light you to the store-room? The maids would have done so, but you would not let them.” “The stranger,” said Telemachus, “shall show me a light; when people eat my bread they must earn it, no matter where they come from.” Euryclea did as she was told, and bolted the women inside their room. Then Ulysses and his son made all haste to take the helmets, shields, and spears inside; and Minerva went before them with a gold lamp in her hand that shed a soft and brilliant radiance, whereon Telemachus said, “Father, my eyes behold a great marvel: the walls, with the rafters, crossbeams, and the supports on which they rest are all aglow as with a flaming fire. Surely there is some god here who has come down from heaven.” “Hush,” answered Ulysses, “hold your peace and ask no questions, for this is the manner of the gods. Get you to your bed, and leave me here to talk with your mother and the maids. Your mother in her grief will ask me all sorts of questions.” On this Telemachus went by torch-light to the other side of the inner court, to the room in which he always slept. There he lay in his bed till morning, while Ulysses was left in the cloister pondering on the means whereby with Minerva’s help he might be able to kill the suitors. Then Penelope came down from her room looking like Venus or Diana, and they set her a seat inlaid with scrolls of silver and ivory near the fire in her accustomed place. It had been made by Icmalius and had a footstool all in one piece with the seat itself; and it was covered with a thick fleece: on this she now sat, and the maids came from the women’s room to join her. They set about removing the tables at which the wicked suitors had been dining, and took away the bread that was left, with the cups from which they had drunk. They emptied the embers out of the braziers, and heaped much wood upon them to give both light and heat; but Melantho began to rail at Ulysses a second time and said, “Stranger, do you mean to plague us by hanging about the house all night and spying upon the women? Be off, you wretch, outside, and eat your supper there, or you shall be driven out with a firebrand.” Ulysses scowled at her and answered, “My good woman, why should you be so angry with me? Is it because I am not clean, and my clothes are all in rags, and because I am obliged to go begging about after the manner of tramps and beggars generally? I too was a rich man once, and had a fine house of my own; in those days I gave to many a tramp such as I now am, no matter who he might be nor what he wanted. I had any number of servants, and all the other things which people have who live well and are accounted wealthy, but it pleased Jove to take all away from me; therefore, woman, beware lest you too come to lose that pride and place in which you now wanton above your fellows; have a care lest you get out of favour with your mistress, and lest Ulysses should come home, for there is still a chance that he may do so. Moreover, though he be dead as you think he is, yet by Apollo’s will he has left a son behind him, Telemachus, who will note anything done amiss by the maids in the house, for he is now no longer in his boyhood.” Penelope heard what he was saying and scolded the maid, “Impudent baggage,” said she, “I see how abominably you are behaving, and you shall smart for it. You knew perfectly well, for I told you myself, that I was going to see the stranger and ask him about my husband, for whose sake I am in such continual sorrow.” Then she said to her head waiting woman Eurynome, “Bring a seat with a fleece upon it, for the stranger to sit upon while he tells his story, and listens to what I have to say. I wish to ask him some questions.” Eurynome brought the seat at once and set a fleece upon it, and as soon as Ulysses had sat down Penelope began by saying, “Stranger, I shall first ask you who and whence are you? Tell me of your town and parents.” “Madam,” answered Ulysses, “who on the face of the whole earth can dare to chide with you? Your fame reaches the firmament of heaven itself; you are like some blameless king, who upholds righteousness, as the monarch over a great and valiant nation: the earth yields its wheat and barley, the trees are loaded with fruit, the ewes bring forth lambs, and the sea abounds with fish by reason of his virtues, and his people do good deeds under him. Nevertheless, as I sit here in your house, ask me some other question and do not seek to know my race and family, or you will recall memories that will yet more increase my sorrow. I am full of heaviness, but I ought not to sit weeping and wailing in another person’s house, nor is it well to be thus grieving continually. I shall have one of the servants or even yourself complaining of me, and saying that my eyes swim with tears because I am heavy with wine.” Then Penelope answered, “Stranger, heaven robbed me of all beauty, whether of face or figure, when the Argives set sail for Troy and my dear husband with them. If he were to return and look after my affairs I should be both more respected and should show a better presence to the world. As it is, I am oppressed with care, and with the afflictions which heaven has seen fit to heap upon me. The chiefs from all our islands—Dulichium, Same, and Zacynthus, as also from Ithaca itself, are wooing me against my will and are wasting my estate. I can therefore show no attention to strangers, nor suppliants, nor to people who say that they are skilled artisans, but am all the time broken-hearted about Ulysses. They want me to marry again at once, and I have to invent stratagems in order to deceive them. In the first place heaven put it in my mind to set up a great tambour-frame in my room, and to begin working upon an enormous piece of fine needlework. Then I said to them, ‘Sweethearts, Ulysses is indeed dead, still, do not press me to marry again immediately; wait—for I would not have my skill in needlework perish unrecorded—till I have finished making a pall for the hero Laertes, to be ready against the time when death shall take him. He is very rich, and the women of the place will talk if he is laid out without a pall.’ This was what I said, and they assented; whereon I used to keep working at my great web all day long, but at night I would unpick the stitches again by torch light. I fooled them in this way for three years without their finding it out, but as time wore on and I was now in my fourth year, in the waning of moons, and many days had been accomplished, those good for nothing hussies my maids betrayed me to the suitors, who broke in upon me and caught me; they were very angry with me, so I was forced to finish my work whether I would or no. And now I do not see how I can find any further shift for getting out of this marriage. My parents are putting great pressure upon me, and my son chafes at the ravages the suitors are making upon his estate, for he is now old enough to understand all about it and is perfectly able to look after his own affairs, for heaven has blessed him with an excellent disposition. Still, notwithstanding all this, tell me who you are and where you come from—for you must have had father and mother of some sort; you cannot be the son of an oak or of a rock.” Then Ulysses answered, “Madam, wife of Ulysses, since you persist in asking me about my family, I will answer, no matter what it costs me: people must expect to be pained when they have been exiles as long as I have, and suffered as much among as many peoples. Nevertheless, as regards your question I will tell you all you ask. There is a fair and fruitful island in mid-ocean called Crete; it is thickly peopled and there are ninety cities in it: the people speak many different languages which overlap one another, for there are Achaeans, brave Eteocretans, Dorians of three-fold race, and noble Pelasgi. There is a great town there, Cnossus, where Minos reigned who every nine years had a conference with Jove himself.152 Minos was father to Deucalion, whose son I am, for Deucalion had two sons Idomeneus and myself. Idomeneus sailed for Troy, and I, who am the younger, am called Aethon; my brother, however, was at once the older and the more valiant of the two; hence it was in Crete that I saw Ulysses and showed him hospitality, for the winds took him there as he was on his way to Troy, carrying him out of his course from cape Malea and leaving him in Amnisus off the cave of Ilithuia, where the harbours are difficult to enter and he could hardly find shelter from the winds that were then raging. As soon as he got there he went into the town and asked for Idomeneus, claiming to be his old and valued friend, but Idomeneus had already set sail for Troy some ten or twelve days earlier, so I took him to my own house and showed him every kind of hospitality, for I had abundance of everything. Moreover, I fed the men who were with him with barley meal from the public store, and got subscriptions of wine and oxen for them to sacrifice to their heart’s content. They stayed with me twelve days, for there was a gale blowing from the North so strong that one could hardly keep one’s feet on land. I suppose some unfriendly god had raised it for them, but on the thirteenth day the wind dropped, and they got away.” Many a plausible tale did Ulysses further tell her, and Penelope wept as she listened, for her heart was melted. As the snow wastes upon the mountain tops when the winds from South East and West have breathed upon it and thawed it till the rivers run bank full with water, even so did her cheeks overflow with tears for the husband who was all the time sitting by her side. Ulysses felt for her and was sorry for her, but he kept his eyes as hard as horn or iron without letting them so much as quiver, so cunningly did he restrain his tears. Then, when she had relieved herself by weeping, she turned to him again and said: “Now, stranger, I shall put you to the test and see whether or no you really did entertain my husband and his men, as you say you did. Tell me, then, how he was dressed, what kind of a man he was to look at, and so also with his companions.” “Madam,” answered Ulysses, “it is such a long time ago that I can hardly say. Twenty years are come and gone since he left my home, and went elsewhither; but I will tell you as well as I can recollect. Ulysses wore a mantle of purple wool, double lined, and it was fastened by a gold brooch with two catches for the pin. On the face of this there was a device that shewed a dog holding a spotted fawn between his fore paws, and watching it as it lay panting upon the ground. Every one marvelled at the way in which these things had been done in gold, the dog looking at the fawn, and strangling it, while the fawn was struggling convulsively to escape.153 As for the shirt that he wore next his skin, it was so soft that it fitted him like the skin of an onion, and glistened in the sunlight to the admiration of all the women who beheld it. Furthermore I say, and lay my saying to your heart, that I do not know whether Ulysses wore these clothes when he left home, or whether one of his companions had given them to him while he was on his voyage; or possibly some one at whose house he was staying made him a present of them, for he was a man of many friends and had few equals among the Achaeans. I myself gave him a sword of bronze and a beautiful purple mantle, double lined, with a shirt that went down to his feet, and I sent him on board his ship with every mark of honour. He had a servant with him, a little older than himself, and I can tell you what he was like; his shoulders were hunched,154 he was dark, and he had thick curly hair. His name was Eurybates, and Ulysses treated him with greater familiarity than he did any of the others, as being the most like-minded with himself.” Penelope was moved still more deeply as she heard the indisputable proofs that Ulysses laid before her; and when she had again found relief in tears she said to him, “Stranger, I was already disposed to pity you, but henceforth you shall be honoured and made welcome in my house. It was I who gave Ulysses the clothes you speak of. I took them out of the store room and folded them up myself, and I gave him also the gold brooch to wear as an ornament. Alas! I shall never welcome him home again. It was by an ill fate that he ever set out for that detested city whose very name I cannot bring myself even to mention.” Then Ulysses answered, “Madam, wife of Ulysses, do not disfigure yourself further by grieving thus bitterly for your loss, though I can hardly blame you for doing so. A woman who has loved her husband and borne him children, would naturally be grieved at losing him, even though he were a worse man than Ulysses, who they say was like a god. Still, cease your tears and listen to what I can tell you. I will hide nothing from you, and can say with perfect truth that I have lately heard of Ulysses as being alive and on his way home; he is among the Thesprotians, and is bringing back much valuable treasure that he has begged from one and another of them; but his ship and all his crew were lost as they were leaving the Thrinacian island, for Jove and the sun-god were angry with him because his men had slaughtered the sun-god’s cattle, and they were all drowned to a man. But Ulysses stuck to the keel of the ship and was drifted on to the land of the Phaeacians, who are near of kin to the immortals, and who treated him as though he had been a god, giving him many presents, and wishing to escort him home safe and sound. In fact Ulysses would have been here long ago, had he not thought better to go from land to land gathering wealth; for there is no man living who is so wily as he is; there is no one can compare with him. Pheidon king of the Thesprotians told me all this, and he swore to me—making drink-offerings in his house as he did so—that the ship was by the water side and the crew found who would take Ulysses to his own country. He sent me off first, for there happened to be a Thesprotian ship sailing for the wheat-growing island of Dulichium, but he showed me all the treasure Ulysses had got together, and he had enough lying in the house of king Pheidon to keep his family for ten generations; but the king said Ulysses had gone to Dodona that he might learn Jove’s mind from the high oak tree, and know whether after so long an absence he should return to Ithaca openly or in secret. So you may know he is safe and will be here shortly; he is close at hand and cannot remain away from home much longer; nevertheless I will confirm my words with an oath, and call Jove who is the first and mightiest of all gods to witness, as also that hearth of Ulysses to which I have now come, that all I have spoken shall surely come to pass. Ulysses will return in this self same year; with the end of this moon and the beginning of the next he will be here.” “May it be even so,” answered Penelope; “if your words come true you shall have such gifts and such good will from me that all who see you shall congratulate you; but I know very well how it will be. Ulysses will not return, neither will you get your escort hence, for so surely as that Ulysses ever was, there are now no longer any such masters in the house as he was, to receive honourable strangers or to further them on their way home. And now, you maids, wash his feet for him, and make him a bed on a couch with rugs and blankets, that he may be warm and quiet till morning. Then, at day break wash him and anoint him again, that he may sit in the cloister and take his meals with Telemachus. It shall be the worse for any one of these hateful people who is uncivil to him; like it or not, he shall have no more to do in this house. For how, sir, shall you be able to learn whether or no I am superior to others of my sex both in goodness of heart and understanding, if I let you dine in my cloisters squalid and ill clad? Men live but for a little season; if they are hard, and deal hardly, people wish them ill so long as they are alive, and speak contemptuously of them when they are dead, but he that is righteous and deals righteously, the people tell of his praise among all lands, and many shall call him blessed.” Ulysses answered, “Madam, I have foresworn rugs and blankets from the day that I left the snowy ranges of Crete to go on shipboard. I will lie as I have lain on many a sleepless night hitherto. Night after night have I passed in any rough sleeping place, and waited for morning. Nor, again, do I like having my feet washed; I shall not let any of the young hussies about your house touch my feet; but, if you have any old and respectable woman who has gone through as much trouble as I have, I will allow her to wash them.” To this Penelope said, “My dear sir, of all the guests who ever yet came to my house there never was one who spoke in all things with such admirable propriety as you do. There happens to be in the house a most respectable old woman—the same who received my poor dear husband in her arms the night he was born, and nursed him in infancy. She is very feeble now, but she shall wash your feet.” “Come here,” said she, “Euryclea, and wash your master’s age-mate; I suppose Ulysses’ hands and feet are very much the same now as his are, for trouble ages all of us dreadfully fast.” On these words the old woman covered her face with her hands; she began to weep and made lamentation saying, “My dear child, I cannot think whatever I am to do with you. I am certain no one was ever more god-fearing than yourself, and yet Jove hates you. No one in the whole world ever burned him more thigh bones, nor gave him finer hecatombs when you prayed you might come to a green old age yourself and see your son grow up to take after you: yet see how he has prevented you alone from ever getting back to your own home. I have no doubt the women in some foreign palace which Ulysses has got to are gibing at him as all these sluts here have been gibing at you. I do not wonder at your not choosing to let them wash you after the manner in which they have insulted you; I will wash your feet myself gladly enough, as Penelope has said that I am to do so; I will wash them both for Penelope’s sake and for your own, for you have raised the most lively feelings of compassion in my mind; and let me say this moreover, which pray attend to; we have had all kinds of strangers in distress come here before now, but I make bold to say that no one ever yet came who was so like Ulysses in figure, voice, and feet as you are.” “Those who have seen us both,” answered Ulysses, “have always said we were wonderfully like each other, and now you have noticed it too.” Then the old woman took the cauldron in which she was going to wash his feet, and poured plenty of cold water into it, adding hot till the bath was warm enough. Ulysses sat by the fire, but ere long he turned away from the light, for it occurred to him that when the old woman had hold of his leg she would recognise a certain scar which it bore, whereon the whole truth would come out. And indeed as soon as she began washing her master, she at once knew the scar as one that had been given him by a wild boar when he was hunting on Mt. Parnassus with his excellent grandfather Autolycus—who was the most accomplished thief and perjurer in the whole world—and with the sons of Autolycus. Mercury himself had endowed him with this gift, for he used to burn the thigh bones of goats and kids to him, so he took pleasure in his companionship. It happened once that Autolycus had gone to Ithaca and had found the child of his daughter just born. As soon as he had done supper Euryclea set the infant upon his knees and said, “Autolycus, you must find a name for your grandson; you greatly wished that you might have one.” “Son-in-law and daughter,” replied Autolycus, “call the child thus: I am highly displeased with a large number of people in one place and another, both men and women; so name the child ‘Ulysses,’ or the child of anger. When he grows up and comes to visit his mother’s family on Mt. Parnassus, where my possessions lie, I will make him a present and will send him on his way rejoicing.” Ulysses, therefore, went to Parnassus to get the presents from Autolycus, who with his sons shook hands with him and gave him welcome. His grandmother Amphithea threw her arms about him, and kissed his head, and both his beautiful eyes, while Autolycus desired his sons to get dinner ready, and they did as he told them. They brought in a five year old bull, flayed it, made it ready and divided it into joints; these they then cut carefully up into smaller pieces and spitted them; they roasted them sufficiently and served the portions round. Thus through the livelong day to the going down of the sun they feasted, and every man had his full share so that all were satisfied; but when the sun set and it came on dark, they went to bed and enjoyed the boon of sleep. When the child of morning, rosy-fingered Dawn, appeared, the sons of Autolycus went out with their hounds hunting, and Ulysses went too. They climbed the wooded slopes of Parnassus and soon reached its breezy upland valleys; but as the sun was beginning to beat upon the fields, fresh-risen from the slow still currents of Oceanus, they came to a mountain dell. The dogs were in front searching for the tracks of the beast they were chasing, and after them came the sons of Autolycus, among whom was Ulysses, close behind the dogs, and he had a long spear in his hand. Here was the lair of a huge boar among some thick brushwood, so dense that the wind and rain could not get through it, nor could the sun’s rays pierce it, and the ground underneath lay thick with fallen leaves. The boar heard the noise of the men’s feet, and the hounds baying on every side as the huntsmen came up to him, so he rushed from his lair, raised the bristles on his neck, and stood at bay with fire flashing from his eyes. Ulysses was the first to raise his spear and try to drive it into the brute, but the boar was too quick for him, and charged him sideways, ripping him above the knee with a gash that tore deep though it did not reach the bone. As for the boar, Ulysses hit him on the right shoulder, and the point of the spear went right through him, so that he fell groaning in the dust until the life went out of him. The sons of Autolycus busied themselves with the carcass of the boar, and bound Ulysses’ wound; then, after saying a spell to stop the bleeding, they went home as fast as they could. But when Autolycus and his sons had thoroughly healed Ulysses, they made him some splendid presents, and sent him back to Ithaca with much mutual good will. When he got back, his father and mother were rejoiced to see him, and asked him all about it, and how he had hurt himself to get the scar; so he told them how the boar had ripped him when he was out hunting with Autolycus and his sons on Mt. Parnassus. As soon as Euryclea had got the scarred limb in her hands and had well hold of it, she recognised it and dropped the foot at once. The leg fell into the bath, which rang out and was overturned, so that all the water was spilt on the ground; Euryclea’s eyes between her joy and her grief filled with tears, and she could not speak, but she caught Ulysses by the beard and said, “My dear child, I am sure you must be Ulysses himself, only I did not know you till I had actually touched and handled you.” As she spoke she looked towards Penelope, as though wanting to tell her that her dear husband was in the house, but Penelope was unable to look in that direction and observe what was going on, for Minerva had diverted her attention; so Ulysses caught Euryclea by the throat with his right hand and with his left drew her close to him, and said, “Nurse, do you wish to be the ruin of me, you who nursed me at your own breast, now that after twenty years of wandering I am at last come to my own home again? Since it has been borne in upon you by heaven to recognise me, hold your tongue, and do not say a word about it to any one else in the house, for if you do I tell you—and it shall surely be—that if heaven grants me to take the lives of these suitors, I will not spare you, though you are my own nurse, when I am killing the other women.” “My child,” answered Euryclea, “what are you talking about? You know very well that nothing can either bend or break me. I will hold my tongue like a stone or a piece of iron; furthermore let me say, and lay my saying to your heart, when heaven has delivered the suitors into your hand, I will give you a list of the women in the house who have been ill-behaved, and of those who are guiltless.” And Ulysses answered, “Nurse, you ought not to speak in that way; I am well able to form my own opinion about one and all of them; hold your tongue and leave everything to heaven.” As he said this Euryclea left the cloister to fetch some more water, for the first had been all spilt; and when she had washed him and anointed him with oil, Ulysses drew his seat nearer to the fire to warm himself, and hid the scar under his rags. Then Penelope began talking to him and said: “Stranger, I should like to speak with you briefly about another matter. It is indeed nearly bed time—for those, at least, who can sleep in spite of sorrow. As for myself, heaven has given me a life of such unmeasurable woe, that even by day when I am attending to my duties and looking after the servants, I am still weeping and lamenting during the whole time; then, when night comes, and we all of us go to bed, I lie awake thinking, and my heart becomes a prey to the most incessant and cruel tortures. As the dun nightingale, daughter of Pandareus, sings in the early spring from her seat in shadiest covert hid, and with many a plaintive trill pours out the tale how by mishap she killed her own child Itylus, son of king Zethus, even so does my mind toss and turn in its uncertainty whether I ought to stay with my son here, and safeguard my substance, my bondsmen, and the greatness of my house, out of regard to public opinion and the memory of my late husband, or whether it is not now time for me to go with the best of these suitors who are wooing me and making me such magnificent presents. As long as my son was still young, and unable to understand, he would not hear of my leaving my husband’s house, but now that he is full grown he begs and prays me to do so, being incensed at the way in which the suitors are eating up his property. Listen, then, to a dream that I have had and interpret it for me if you can. I have twenty geese about the house that eat mash out of a trough,155 and of which I am exceedingly fond. I dreamed that a great eagle came swooping down from a mountain, and dug his curved beak into the neck of each of them till he had killed them all. Presently he soared off into the sky, and left them lying dead about the yard; whereon I wept in my dream till all my maids gathered round me, so piteously was I grieving because the eagle had killed my geese. Then he came back again, and perching on a projecting rafter spoke to me with human voice, and told me to leave off crying. ‘Be of good courage,’ he said, ‘daughter of Icarius; this is no dream, but a vision of good omen that shall surely come to pass. The geese are the suitors, and I am no longer an eagle, but your own husband, who am come back to you, and who will bring these suitors to a disgraceful end.’ On this I woke, and when I looked out I saw my geese at the trough eating their mash as usual.” “This dream, Madam,” replied Ulysses, “can admit but of one interpretation, for had not Ulysses himself told you how it shall be fulfilled? The death of the suitors is portended, and not one single one of them will escape.” And Penelope answered, “Stranger, dreams are very curious and unaccountable things, and they do not by any means invariably come true. There are two gates through which these unsubstantial fancies proceed; the one is of horn, and the other ivory. Those that come through the gate of ivory are fatuous, but those from the gate of horn mean something to those that see them. I do not think, however, that my own dream came through the gate of horn, though I and my son should be most thankful if it proves to have done so. Furthermore I say—and lay my saying to your heart—the coming dawn will usher in the ill-omened day that is to sever me from the house of Ulysses, for I am about to hold a tournament of axes. My husband used to set up twelve axes in the court, one in front of the other, like the stays upon which a ship is built; he would then go back from them and shoot an arrow through the whole twelve. I shall make the suitors try to do the same thing, and whichever of them can string the bow most easily, and send his arrow through all the twelve axes, him will I follow, and quit this house of my lawful husband, so goodly and so abounding in wealth. But even so, I doubt not that I shall remember it in my dreams.” Then Ulysses answered, “Madam, wife of Ulysses, you need not defer your tournament, for Ulysses will return ere ever they can string the bow, handle it how they will, and send their arrows through the iron.” To this Penelope said, “As long, sir, as you will sit here and talk to me, I can have no desire to go to bed. Still, people cannot do permanently without sleep, and heaven has appointed us dwellers on earth a time for all things. I will therefore go upstairs and recline upon that couch which I have never ceased to flood with my tears from the day Ulysses set out for the city with a hateful name.” She then went upstairs to her own room, not alone, but attended by her maidens, and when there, she lamented her dear husband till Minerva shed sweet sleep over her eyelids.

book_20.txt

BOOK XX ULYSSES CANNOT SLEEP—PENELOPE’S PRAYER TO DIANA—THE TWO SIGNS FROM HEAVEN—EUMAEUS AND PHILOETIUS ARRIVE—THE SUITORS DINE—CTESIPPUS THROWS AN OX’S FOOT AT ULYSSES—THEOCLYMENUS FORETELLS DISASTER AND LEAVES THE HOUSE. Ulysses slept in the cloister upon an undressed bullock’s hide, on the top of which he threw several skins of the sheep the suitors had eaten, and Eurynome156 threw a cloak over him after he had laid himself down. There, then, Ulysses lay wakefully brooding upon the way in which he should kill the suitors; and by and by, the women who had been in the habit of misconducting themselves with them, left the house giggling and laughing with one another. This made Ulysses very angry, and he doubted whether to get up and kill every single one of them then and there, or to let them sleep one more and last time with the suitors. His heart growled within him, and as a bitch with puppies growls and shows her teeth when she sees a stranger, so did his heart growl with anger at the evil deeds that were being done: but he beat his breast and said, “Heart, be still, you had worse than this to bear on the day when the terrible Cyclops ate your brave companions; yet you bore it in silence till your cunning got you safe out of the cave, though you made sure of being killed.” Thus he chided with his heart, and checked it into endurance, but he tossed about as one who turns a paunch full of blood and fat in front of a hot fire, doing it first on one side and then on the other, that he may get it cooked as soon as possible, even so did he turn himself about from side to side, thinking all the time how, single handed as he was, he should contrive to kill so large a body of men as the wicked suitors. But by and by Minerva came down from heaven in the likeness of a woman, and hovered over his head saying, “My poor unhappy man, why do you lie awake in this way? This is your house: your wife is safe inside it, and so is your son who is just such a young man as any father may be proud of.” “Goddess,” answered Ulysses, “all that you have said is true, but I am in some doubt as to how I shall be able to kill these wicked suitors single handed, seeing what a number of them there always are. And there is this further difficulty, which is still more considerable. Supposing that with Jove’s and your assistance I succeed in killing them, I must ask you to consider where I am to escape to from their avengers when it is all over.” “For shame,” replied Minerva, “why, any one else would trust a worse ally than myself, even though that ally were only a mortal and less wise than I am. Am I not a goddess, and have I not protected you throughout in all your troubles? I tell you plainly that even though there were fifty bands of men surrounding us and eager to kill us, you should take all their sheep and cattle, and drive them away with you. But go to sleep; it is a very bad thing to lie awake all night, and you shall be out of your troubles before long.” As she spoke she shed sleep over his eyes, and then went back to Olympus. While Ulysses was thus yielding himself to a very deep slumber that eased the burden of his sorrows, his admirable wife awoke, and sitting up in her bed began to cry. When she had relieved herself by weeping she prayed to Diana saying, “Great Goddess Diana, daughter of Jove, drive an arrow into my heart and slay me; or let some whirlwind snatch me up and bear me through paths of darkness till it drop me into the mouths of over-flowing Oceanus, as it did the daughters of Pandareus. The daughters of Pandareus lost their father and mother, for the gods killed them, so they were left orphans. But Venus took care of them, and fed them on cheese, honey, and sweet wine. Juno taught them to excel all women in beauty of form and understanding; Diana gave them an imposing presence, and Minerva endowed them with every kind of accomplishment; but one day when Venus had gone up to Olympus to see Jove about getting them married (for well does he know both what shall happen and what not happen to every one) the storm winds came and spirited them away to become handmaids to the dread Erinyes. Even so I wish that the gods who live in heaven would hide me from mortal sight, or that fair Diana might strike me, for I would fain go even beneath the sad earth if I might do so still looking towards Ulysses only, and without having to yield myself to a worse man than he was. Besides, no matter how much people may grieve by day, they can put up with it so long as they can sleep at night, for when the eyes are closed in slumber people forget good and ill alike; whereas my misery haunts me even in my dreams. This very night methought there was one lying by my side who was like Ulysses as he was when he went away with his host, and I rejoiced, for I believed that it was no dream, but the very truth itself.” On this the day broke, but Ulysses heard the sound of her weeping, and it puzzled him, for it seemed as though she already knew him and was by his side. Then he gathered up the cloak and the fleeces on which he had lain, and set them on a seat in the cloister, but he took the bullock’s hide out into the open. He lifted up his hands to heaven, and prayed, saying “Father Jove, since you have seen fit to bring me over land and sea to my own home after all the afflictions you have laid upon me, give me a sign out of the mouth of some one or other of those who are now waking within the house, and let me have another sign of some kind from outside.” Thus did he pray. Jove heard his prayer and forthwith thundered high up among the clouds from the splendour of Olympus, and Ulysses was glad when he heard it. At the same time within the house, a miller-woman from hard by in the mill room lifted up her voice and gave him another sign. There were twelve miller-women whose business it was to grind wheat and barley which are the staff of life. The others had ground their task and had gone to take their rest, but this one had not yet finished, for she was not so strong as they were, and when she heard the thunder she stopped grinding and gave the sign to her master. “Father Jove,” said she, “you, who rule over heaven and earth, you have thundered from a clear sky without so much as a cloud in it, and this means something for somebody; grant the prayer, then, of me your poor servant who calls upon you, and let this be the very last day that the suitors dine in the house of Ulysses. They have worn me out with labour of grinding meal for them, and I hope they may never have another dinner anywhere at all.” Ulysses was glad when he heard the omens conveyed to him by the woman’s speech, and by the thunder, for he knew they meant that he should avenge himself on the suitors. Then the other maids in the house rose and lit the fire on the hearth; Telemachus also rose and put on his clothes. He girded his sword about his shoulder, bound his sandals on to his comely feet, and took a doughty spear with a point of sharpened bronze; then he went to the threshold of the cloister and said to Euryclea, “Nurse, did you make the stranger comfortable both as regards bed and board, or did you let him shift for himself?—for my mother, good woman though she is, has a way of paying great attention to second-rate people, and of neglecting others who are in reality much better men.” “Do not find fault child,” said Euryclea, “when there is no one to find fault with. The stranger sat and drank his wine as long as he liked: your mother did ask him if he would take any more bread and he said he would not. When he wanted to go to bed she told the servants to make one for him, but he said he was such a wretched outcast that he would not sleep on a bed and under blankets; he insisted on having an undressed bullock’s hide and some sheepskins put for him in the cloister and I threw a cloak over him myself.”157 Then Telemachus went out of the court to the place where the Achaeans were meeting in assembly; he had his spear in his hand, and he was not alone, for his two dogs went with him. But Euryclea called the maids and said, “Come, wake up; set about sweeping the cloisters and sprinkling them with water to lay the dust; put the covers on the seats; wipe down the tables, some of you, with a wet sponge; clean out the mixing-jugs and the cups, and go for water from the fountain at once; the suitors will be here directly; they will be here early, for it is a feast day.” Thus did she speak, and they did even as she had said: twenty of them went to the fountain for water, and the others set themselves busily to work about the house. The men who were in attendance on the suitors also came up and began chopping firewood. By and by the women returned from the fountain, and the swineherd came after them with the three best pigs he could pick out. These he let feed about the premises, and then he said good-humouredly to Ulysses, “Stranger, are the suitors treating you any better now, or are they as insolent as ever?” “May heaven,” answered Ulysses, “requite to them the wickedness with which they deal high-handedly in another man’s house without any sense of shame.” Thus did they converse; meanwhile Melanthius the goatherd came up, for he too was bringing in his best goats for the suitors’ dinner; and he had two shepherds with him. They tied the goats up under the gatehouse, and then Melanthius began gibing at Ulysses. “Are you still here, stranger,” said he, “to pester people by begging about the house? Why can you not go elsewhere? You and I shall not come to an understanding before we have given each other a taste of our fists. You beg without any sense of decency: are there not feasts elsewhere among the Achaeans, as well as here?” Ulysses made no answer, but bowed his head and brooded. Then a third man, Philoetius, joined them, who was bringing in a barren heifer and some goats. These were brought over by the boatmen who are there to take people over when any one comes to them. So Philoetius made his heifer and his goats secure under the gatehouse, and then went up to the swineherd. “Who, Swineherd,” said he, “is this stranger that is lately come here? Is he one of your men? What is his family? Where does he come from? Poor fellow, he looks as if he had been some great man, but the gods give sorrow to whom they will—even to kings if it so pleases them.” As he spoke he went up to Ulysses and saluted him with his right hand; “Good day to you, father stranger,” said he, “you seem to be very poorly off now, but I hope you will have better times by and by. Father Jove, of all gods you are the most malicious. We are your own children, yet you show us no mercy in all our misery and afflictions. A sweat came over me when I saw this man, and my eyes filled with tears, for he reminds me of Ulysses, who I fear is going about in just such rags as this man’s are, if indeed he is still among the living. If he is already dead and in the house of Hades, then, alas! for my good master, who made me his stockman when I was quite young among the Cephallenians, and now his cattle are countless; no one could have done better with them than I have, for they have bred like ears of corn; nevertheless I have to keep bringing them in for others to eat, who take no heed to his son though he is in the house, and fear not the wrath of heaven, but are already eager to divide Ulysses’ property among them because he has been away so long. I have often thought—only it would not be right while his son is living—of going off with the cattle to some foreign country; bad as this would be, it is still harder to stay here and be ill-treated about other people’s herds. My position is intolerable, and I should long since have run away and put myself under the protection of some other chief, only that I believe my poor master will yet return, and send all these suitors flying out of the house.” “Stockman,” answered Ulysses, “you seem to be a very well-disposed person, and I can see that you are a man of sense. Therefore I will tell you, and will confirm my words with an oath. By Jove, the chief of all gods, and by that hearth of Ulysses to which I am now come, Ulysses shall return before you leave this place, and if you are so minded you shall see him killing the suitors who are now masters here.” “If Jove were to bring this to pass,” replied the stockman, “you should see how I would do my very utmost to help him.” And in like manner Eumaeus prayed that Ulysses might return home. Thus did they converse. Meanwhile the suitors were hatching a plot to murder Telemachus: but a bird flew near them on their left hand—an eagle with a dove in its talons. On this Amphinomus said, “My friends, this plot of ours to murder Telemachus will not succeed; let us go to dinner instead.” The others assented, so they went inside and laid their cloaks on the benches and seats. They sacrificed the sheep, goats, pigs, and the heifer, and when the inward meats were cooked they served them round. They mixed the wine in the mixing-bowls, and the swineherd gave every man his cup, while Philoetius handed round the bread in the bread baskets, and Melanthius poured them out their wine. Then they laid their hands upon the good things that were before them. Telemachus purposely made Ulysses sit in the part of the cloister that was paved with stone;158 he gave him a shabby looking seat at a little table to himself, and had his portion of the inward meats brought to him, with his wine in a gold cup. “Sit there,” said he, “and drink your wine among the great people. I will put a stop to the gibes and blows of the suitors, for this is no public house, but belongs to Ulysses, and has passed from him to me. Therefore, suitors, keep your hands and your tongues to yourselves, or there will be mischief.” The suitors bit their lips, and marvelled at the boldness of his speech; then Antinous said, “We do not like such language but we will put up with it, for Telemachus is threatening us in good earnest. If Jove had let us we should have put a stop to his brave talk ere now.” Thus spoke Antinous, but Telemachus heeded him not. Meanwhile the heralds were bringing the holy hecatomb through the city, and the Achaeans gathered under the shady grove of Apollo. Then they roasted the outer meat, drew it off the spits, gave every man his portion, and feasted to their heart’s content; those who waited at table gave Ulysses exactly the same portion as the others had, for Telemachus had told them to do so. But Minerva would not let the suitors for one moment drop their insolence, for she wanted Ulysses to become still more bitter against them. Now there happened to be among them a ribald fellow, whose name was Ctesippus, and who came from Same. This man, confident in his great wealth, was paying court to the wife of Ulysses, and said to the suitors, “Hear what I have to say. The stranger has already had as large a portion as any one else; this is well, for it is not right nor reasonable to ill-treat any guest of Telemachus who comes here. I will, however, make him a present on my own account, that he may have something to give to the bath-woman, or to some other of Ulysses’ servants.” As he spoke he picked up a heifer’s foot from the meat-basket in which it lay, and threw it at Ulysses, but Ulysses turned his head a little aside, and avoided it, smiling grimly Sardinian fashion159 as he did so, and it hit the wall, not him. On this Telemachus spoke fiercely to Ctesippus, “It is a good thing for you,” said he, “that the stranger turned his head so that you missed him. If you had hit him I should have run you through with my spear, and your father would have had to see about getting you buried rather than married in this house. So let me have no more unseemly behaviour from any of you, for I am grown up now to the knowledge of good and evil and understand what is going on, instead of being the child that I have been heretofore. I have long seen you killing my sheep and making free with my corn and wine: I have put up with this, for one man is no match for many, but do me no further violence. Still, if you wish to kill me, kill me; I would far rather die than see such disgraceful scenes day after day—guests insulted, and men dragging the women servants about the house in an unseemly way.” They all held their peace till at last Agelaus son of Damastor said, “No one should take offence at what has just been said, nor gainsay it, for it is quite reasonable. Leave off, therefore, ill-treating the stranger, or any one else of the servants who are about the house; I would say, however, a friendly word to Telemachus and his mother, which I trust may commend itself to both. ‘As long,’ I would say, ‘as you had ground for hoping that Ulysses would one day come home, no one could complain of your waiting and suffering160 the suitors to be in your house. It would have been better that he should have returned, but it is now sufficiently clear that he will never do so; therefore talk all this quietly over with your mother, and tell her to marry the best man, and the one who makes her the most advantageous offer. Thus you will yourself be able to manage your own inheritance, and to eat and drink in peace, while your mother will look after some other man’s house, not yours.’” To this Telemachus answered, “By Jove, Agelaus, and by the sorrows of my unhappy father, who has either perished far from Ithaca, or is wandering in some distant land, I throw no obstacles in the way of my mother’s marriage; on the contrary I urge her to choose whomsoever she will, and I will give her numberless gifts into the bargain, but I dare not insist point blank that she shall leave the house against her own wishes. Heaven forbid that I should do this.” Minerva now made the suitors fall to laughing immoderately, and set their wits wandering; but they were laughing with a forced laughter. Their meat became smeared with blood; their eyes filled with tears, and their hearts were heavy with forebodings. Theoclymenus saw this and said, “Unhappy men, what is it that ails you? There is a shroud of darkness drawn over you from head to foot, your cheeks are wet with tears; the air is alive with wailing voices; the walls and roof-beams drip blood; the gate of the cloisters and the court beyond them are full of ghosts trooping down into the night of hell; the sun is blotted out of heaven, and a blighting gloom is over all the land.” Thus did he speak, and they all of them laughed heartily. Eurymachus then said, “This stranger who has lately come here has lost his senses. Servants, turn him out into the streets, since he finds it so dark here.” But Theoclymenus said, “Eurymachus, you need not send any one with me. I have eyes, ears, and a pair of feet of my own, to say nothing of an understanding mind. I will take these out of the house with me, for I see mischief overhanging you, from which not one of you men who are insulting people and plotting ill deeds in the house of Ulysses will be able to escape.” He left the house as he spoke, and went back to Piraeus who gave him welcome, but the suitors kept looking at one another and provoking Telemachus by laughing at the strangers. One insolent fellow said to him, “Telemachus, you are not happy in your guests; first you have this importunate tramp, who comes begging bread and wine and has no skill for work or for hard fighting, but is perfectly useless, and now here is another fellow who is setting himself up as a prophet. Let me persuade you, for it will be much better to put them on board ship and send them off to the Sicels to sell for what they will bring.” Telemachus gave him no heed, but sat silently watching his father, expecting every moment that he would begin his attack upon the suitors. Meanwhile the daughter of Icarius, wise Penelope, had had a rich seat placed for her facing the court and cloisters, so that she could hear what every one was saying. The dinner indeed had been prepared amid much merriment; it had been both good and abundant, for they had sacrificed many victims; but the supper was yet to come, and nothing can be conceived more gruesome than the meal which a goddess and a brave man were soon to lay before them—for they had brought their doom upon themselves.

Parent

No children (leaf entity)